Project Director’s Message September 2024

Dear Past Wrongs, Future Choices,

The New Canadian astounds me. After Canada declared war on Japan, most Canadian news outlets fell silent on the mistreatment of people of Japanese descent or, worse still, actively stoked racist hysteria. As PWFC scholar in residence Jonathan van Harmelen explains, the media was part of the tragic failure of democracy, and, in this darkness, The New Canadian reads as a beacon of light. The sole Japanese Canadian publication permitted to print, the newspaper informed its readers about the direction of policy, reported on their hardships and anxieties, and challenged the cascade of harms unleashed by federal policy. With digital access to the newspaper now imperilled, its towering achievements of the 1940s deserve recognition. A testament to journalistic courage in the face of a draconian state and a document of the lives of people facing injustice, The New Canadian merits both preservation and admiration.

Established in early 1939 as the “voice of the second generation,” the newspaper faced formidable challenges two years later. In June 1941, The New Canadian urged its readers to buy Victory Bonds in support of the Canadian war effort. “As a Japanese racial minority in British Columbia we recognize the shortcomings of Canadian democracy,” the editors wrote, “[b]ut for the same reason we recognize just what Hitler and his doctrine of racial persecution would mean to us were it to gain even temporary ascendancy.” The paper’s conviction that Japanese Canadians could be part of a Canadian democracy at war would soon be sorely tested.

Six months later, in the days after Japan’s attacks in the Pacific and the outbreak of war, The New Canadian documented its immediate impacts, as Japanese Canadians were thrown out of work. “[S]ection hands, red caps, bell boys, sawmill workers, factory hands, [are] all searching now for a means of living,” the paper reported, while “tradesmen, merchants, and clerks throughout the city wonder about their clientele, wonder if the customers can see beneath the Japanese exterior into the human being. Some gather the remnants of a shattered plate glass window in silence.”

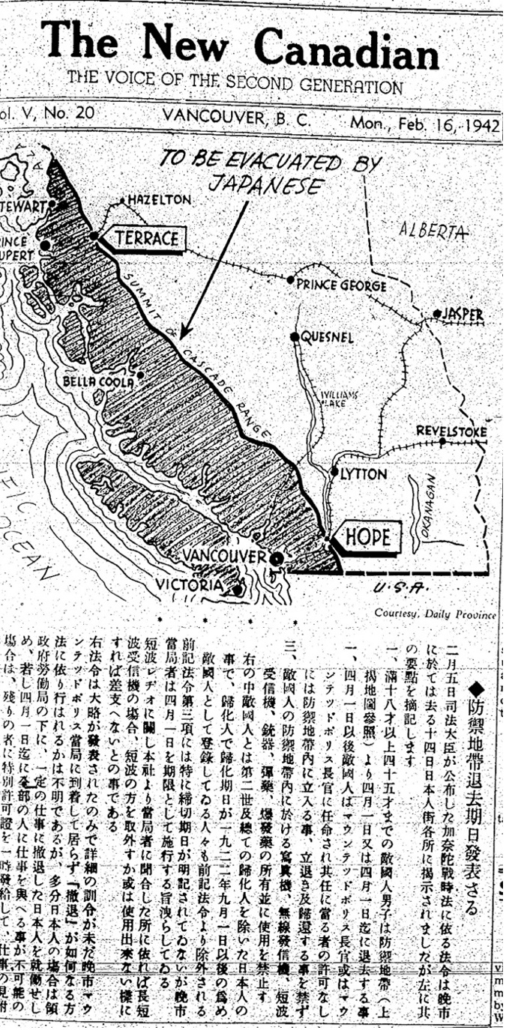

As the government’s policy—the total uprooting of Japanese Canadians from the coast—came into view, The New Canadian informed its uncertain readers about their fates. Integrating a Japanese language section to reach issei readers deprived of their own publications, the paper delivered the hard news:

When the roundups began in March, The New Canadian reported on the demoralizing conditions of Japanese Canadian detainment, contributing to community-based efforts to pressure the government for improvements.

After its forced relocation to Kaslo, a site of internment in the British Columbia interior, the newspaper resumed publication, reporting on the lives of Japanese Canadians, their ongoing strivings for justice, and their efforts to rebuild community in the context of internment. In early September 1944, The New Canadian reported from the Obon festival at the New Denver site:

A gaily decorated pavilion was set up in the middle of the Orchard baseball field, and candle-lit Japanese lanterns were strung about. Nisei girls in bright-colored kimonos danced their ‘odori’ round and round the pavilion to . . . Japanese music. Sometimes, soloists on the pavilion sang into the mike . . . as they became infected by the gaiety of the music and the dancers, more and more began to dance, forming circles within circles around the pavilion.

As the paper documented, sites of internment became more than just the hardships that they entailed. Nonetheless, writers at The New Canadian knew that, whatever sense of belonging they had achieved, Japanese Canadians still lived under threat. “As I stood watching,” explained the writer, “I felt like saying, ‘dance everybody, dance like mad, because life itself is a dance, and something of a joke.”

When a participant on PWFC’s Field School, Larissa Kondo, initiated a campaign to save digital access to The New Canadian, I could not have been prouder. As a result of her efforts, the newspaper will now be available until at least November. Pressure should continue to keep it alive longer. In honour of the unflagging energy of The New Canadian in the 1940s, those of us who love and learn from the paper should join in saving it from obscurity today.

Instagram

Instagram