Andrew’s PWFC Residency Blog

By Andrew Hasegawa, first published on the Nikkei Australia website

When I applied for the Past Wrongs Future Choices scholars’ residency in 2023, I knew my research topic would be of interest to the Project, but I didn’t have much confidence that I’d be awarded a residency. Surely there would be a long line of academics, post-doctoral fellows, and PhD students in the queue in front of me. I’m not an academic. I’m a businessman and independent researcher.

So when I received the news in June 2023 that I’d been chosen to pursue my research during an eight week residency at the University of Victoria in Canada, I was delighted. Brimming with enthusiasm in fact.

I left Australia for Canada in September. Door to door it was 24 hours of travel. I arrived in Vancouver then took the ferry. The day was glorious, expansive blue skies, barely a breath of wind, and the temperature hovered around 20°C. That’s warm in Canada!

Ferry Terminal, Vancouver

The scenery was stunning with the coastline of Washington State to the south, and Vancouver Island to the north on display. Eventually, I reached my accommodation, in need of sleep and food. I took a quick nap before taking a bus into central Victoria.

Remembering the words of the ‘hungry historian’, also known as PWFC Director Jordan Stanger-Ross, I tried a Japanese restaurant he’d recommended called Yua Bistro. The sushi chef greeted me in Japanese, so I replied in Japanese. But he just looked embarrassed, confessing he couldn’t actually speak Japanese, and that he was Korean. This hardly seemed relevant, because the sushi certainly passed the taste test. I then returned to my bed in desperate need of more sleep. Several days of jetlag were still ahead of me.

Mount Baker, Washington State, USA

On my fourth day in Canada, I headed to the University of Victoria to start the process of becoming a student again. It’s been a long time since I graduated university – 37 years to be precise. There was a desk for me at the Centre for Asia Pacific Initiatives (CAPI), where I could work on my research paper. I obtained a student card and the first thing I did was to locate the library.

One of the three other residents had arrived before me – Kunji Ikeda, an artist and dancer. Over the next week, Lon Kurashige, Professor of History at the University of Southern California, followed by Nao Uda, an artist and PhD candidate also arrived.

And once all the residents were assembled, there was a series of events beginning with a tour of Victoria with Mike Abe, PWFC Project Manager, and lectures by visiting scholars. There were dinners and lunches. Some were organised events, others impromptu. Yasuko Takezawa, formerly of Kyoto University, gave a presentation on the outcaste community in Japan – a topic rarely openly discussed – and as she pointed out, the discrimination against the Burakumin continues.

As for my research, I felt I had to begin by learning about the Japanese-American experience during the Pacific War. I was especially intrigued by Mitsuye Endo. She was a private person, and I couldn’t find many documents about her, despite the fact that her challenge against wartime incarceration became the most significant legal case on behalf of Japanese Americans. In contrast, the virtually unknown story of Kojiro Katsumata in Australia generated a large volume of archival material. (More details about my research paper can be found here.)

I felt lucky to have an experienced historian like Lon Kurashige close by during my residency. I spent a lot of time talking to Lon. He was curious about the experiences of Japanese Australians, and he taught me a lot about the history of Japanese Americans. In the post Pacific War era, the Japanese-American community was dominated by nisei (2nd generation) and sansei (3rd generation), who were mostly American citizens. The word ‘Nikkei’ wasn’t a word they used to describe themselves. They wanted to be treated as equals with other Americans. History shows that eventually they were.

Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre (Photo by Mike – /squeakymarmot CC BY-SA 2.0)

The aspect of the residency experience most precious to me was the close bonds forged between the residents. Together we took a trip to Vancouver and the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre. At the Nikkei Museum we were given a guided tour by the Director/Curator Sherri Kajiwara. Sherri, who is involved in the artistic outcomes of the PWFC project, was incredibly generous with her time.

I found the Museum to be a fascinating place. It brings the old and the new Nikkei communities together. Many young Japanese head there to learn Japanese. Many Nikkei people donate family objects. In fact, the Museum’s warehouse is overflowing with objects and photographs that tell the story of the Canadian Japanese. What a contrast this is with Australia, where very few artefacts from the pre-war Nikkei community remain.

The unexpected highlight of our trip to Vancouver was a visit to a sushi restaurant in Port Moody. Nao Uda did her homework and found a restaurant with rave reviews. Run by an elderly Japanese husband and wife, it lived up to the rave expectations. Real sushi at a reasonable price – hard to find in downtown Vancouver. This eatery is called Matsuzushi, run by Toshiaki Hataguchi, who was born in Karafuto (Sakhalin). But he grew up in the Kansai region of Japan, and sitting at the counter speaking to him in Kansai dialect while sipping sake, made me fantasise that I was back in Japan.

Eijun Mitsubori: Japanese confectionary master

The following evening at the Museum, we attended an unusual performance by Eijun Mitsubori, a master Japanese confectionary artist, who created sublimely beautiful wagashi in front of us. He lives in Japan, but was in Canada for a visit. Wagashi will never taste quite the same to me after watching him.

On the Saturday, we headed north to the site of Tashme Internment Camp, where Japanese civilians were forcibly relocated during World War II. Located in a valley in mountainous country, I imagine it would have been miserable and cold during the bitter winters. The one remaining building from the internment era has been converted into a museum, housing many historical objects and photos.

Tashme Internment Camp’s Museum

There is a lot in common between the Australian and Canadian internment experience. Nikkei communities were uprooted, incarcerated, and exiled. But in Canada not everyone was forcibly sent to Japan post-war, in Australia just about everyone was. In Canada many people were dispossessed of their property (real estate), while in Australia this was not the case. An exclusion zone was created in Canada along the west coast, there was none in Australia. The Nikkei in Canada were relocated east post-war, while in Australia people were allowed to decide where to live, with the exception of Darwin. And in Canada, there remained a Nikkei community, large enough to collectively organise and fight for a formal apology and reparations. In Australia, there was no critical mass of people, and the Nikkei who were left were dispersed and separated by the tyranny of distance across a vast continent.

An exclusion zone was created: an act of ethnic cleansing

Most days, I could be found at my desk reading about Mitsuye Endo and the Japanese-American experience. It opened my eyes to another world. Quite frequently I put pen to paper to ensure I was recording what I was researching, and to make sure I was progressing solidly on my research paper. After all, this was the purpose of my residency!

In early November, the four residents presented our research to an audience of students, academics, and members of the public. We each presented for about 15 minutes, followed by a Q and A session. There was interest in the Japanese-Australian experience and I fielded a number of questions. There were questions about why there has never been an apology or reparations made to the Nikkei in Australia.

Presentation Day. Left to Right: Jordan, Lon, Kunji, Andrew, and Nao

My answer was necessarily from a personal perspective – internment meant the closure of the Hasegawa family business, which greatly impacted my great-grandfather, my grandfather and grandmother, as well as my father and his siblings. I believe they should have received compensation for the hardships they endured. But I don’t think it’s appropriate for me, a fourth generation Nikkei Australian, to receive compensation, nor does a belated apology interest me. On the other hand, documenting histories, and telling the stories of what happened to the Nikkei in Australia, not just my family, is very important for me.

My stay in Canada coincided with the Rugby World Cup 2023, and I discovered that the matches were being televised at the Smugglers’ Cove Pub, about a 20 minute walk from where I was living. It was a perfect spot to grab a beer, a bite, and this is where I befriended a small group of retired men who were pub regulars. Over the weeks, they included me into their circle, and invited me to take a trip up north to Lake Cowichan to watch the salmon run.

Along the way there was spectacular scenery. The mountains are steep and the countryside rugged, quite different to Australia, where what we call mountains might best be referred to as pimples. The forests are a deep green, a different hue to a eucalypt forest.

Stunning scenery, Vancouver Island

My mates from the pub were a diverse bunch. John was born in Tanzania in the last days of the British Empire. He went to the UK as a toddler, but his father worked in the mining industry and that eventually brought John to Canada. Mike is British, and migrated to Canada with his young family in the late 1970s. He worked in banking. I loved his British sense of humour. Dave was the only one born in Canada. He is a Sikh and his family came from Punjab. He can still converse in Punjabi, but his preferred language is English. There were others like Gordy the Glaswegian, who used to work in the shipbuilding industry. And there was also the ‘crab man’ who took me out crabbing. Dinner was delicious that night.

Smugglers’ Cove Pub, Victoria, British Columbia

On the way to Lake Cowichan we visited a Sikh temple in a former logging camp named Paldi. These days Paldi is a ghost town with only two residents – the Sikh priest and his wife. The town was populated mainly by Sikhs and the Japanese working in the logging industry in the pre-war years. Inside the temple were photos dating back to the 1930s, and Japanese and Sikh families could be seen together. Services are still held at this temple, and many Sikhs make the journey into the hills to attend on a regular basis.

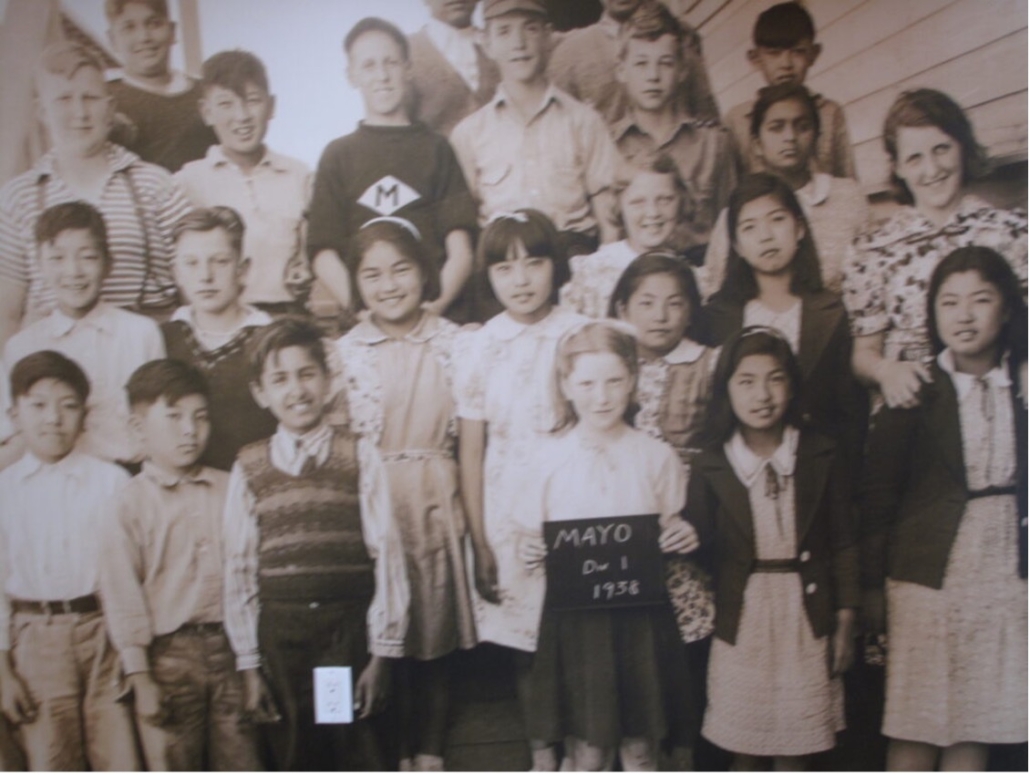

Paldi, Vancouver Island, 1938, school photo

Australians and Canadians have a lot in common – both countries are members of the Commonwealth, and we’ve inherited the same Westminster system of government. But it seemed to me that Victoria was rather ‘waspish’, lacking the ethnic diversity of big cities in Australia.

A long border with the USA means the influence of their neighbour is ever palpable. At the pub, people watch American football, baseball, and basketball. And Canadians speak North American English. I am sure there are regional variations in Canada, though I couldn’t differentiate.

But in the two months of my residency, there was only one occasion when I was stumped by our differences in language. I was told that the supermarket was on the ‘kitty-corner’. Kitty-corner? An interesting conversation with the storekeeper ensued. Eventually he stepped outside and pointed to the kitty corner – diagonally across the road. Well, now I know what it means. It won’t be entering my vocabulary though. Say kitty-corner and I instantly think of kitty litter!

Two months in Canada, having the time of my life researching a subject that I am passionate about! It all seems like a dream now. Amongst the things I’ll never forget are the wild deer roaming the suburban streets of Victoria. Another thing I liked was the bike racks attached to the front of public buses. Such innovation! What really surprised me is that people say ’thank you‘ when getting off the bus. That doesn’t happen in my home town Melbourne. Then there is the magnificent strait that separates Vancouver Island from Washington State, Juan de Fuca. How do you pronounce that? Wonder fucker? Well not quite, but I can’t get that out of my head.

The most important thing to come out of the residency, apart from my working paper of course, is the fact that I made new friends with whom I can share ideas, and collaborate on projects in the future.

Watch out for deer!

All photos supplied by author unless otherwise stated.

Instagram

Instagram