Despite Looting and Deportations… They Never Stopped Loving Peru

By Fernando Nakasone. Originally published, in Spanish, on May 15, 2016

*This English translation by Cath Collins

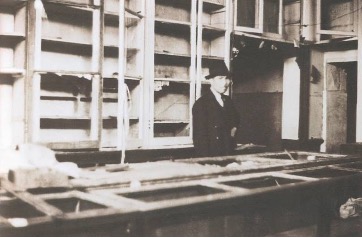

Looted soda warehouse

It was in May 1940 that my obaachan (grandmother), then aged 17, and my ojichan (grandfather) – who was 20 – decided to open their first small business in the town of Huaral. Before that they had worked a small plot of land that my grandfather had in Esquivel. But now, thanks to the help of some of their fellow countrymen, they opened a small grocery store. There was a big empty space at the side of the store that my grandfather decided to turn into a parking lot … for donkeys. The first time I heard that I laughed out loud, but as it happens it was true that lots of people from remote areas came to Huaral, especially on the weekend. Since they travelled by donkey, when they went shopping they would leave their donkey ‘parked’ in the space my grandfather had prepared.

Warehouse belonging to a small business owner, completely looted

Unfortunately, on May 13, 1940 – just a few days after they had opened the business – a mob of people with hate in their hearts, whipped up by the government and the press, looted my grandparents’ tiny shop and businesses belonging to all of the Japanese people of the town. My grandmother, pregnant at just 17 years of age, was carrying my father in her belly, she was just 4 months along. When she saw this horde burst in and start to steal everything they could get their hands on, all she could do was to hide and curl up under one of the counters. And it didn’t only happen there, the same thing occurred in other towns and cities around the country, and most of all in Lima, more than 600 families were affected and at least 10 Japanese people were killed.

Ever since immigration began in 1899, the Japanese started off working as agricultural laborers (peones) on the large landed estates (haciendas), in the worst possible conditions. But with hard work and effort little by little they bettered themselves: many people managed first to rent and then to buy their own small plots of land to plant. Then later they migrated to the cities and became prosperous merchants. That success of the Japanese-owned businesses started to provoke jealousy and irritation among the dominant oligarchy, who began to see it as a threat to their interests.

That’s why in 1936 the government started to bring in laws that limited the entry of more Japanese to the country. Immigration into Peru came to an abrupt halt. Laws started to be passed that meant the Japanese couldn’t hand their businesses on to other foreigners… and as their children had been born in Peru but didn’t have Peruvian nationality, they couldn’t inherit their parents’ businesses. All those measures were brought in to halt the progress of the Japanese. All that hate and envy got even more critical when Japan joined tripartite axis of Rome-Berlin-Tokyo [i.e. became one of WWII’s Axis powers], and even more hate built up against the Japanese.

So that was how rumors got started that the Japanese were really spies for the Japanese empire, and were arming themselves in order to attack the government palace and some cities across Peru. It’s almost impossible to imagine now, but the population believed all these tales. This mixture of paranoia and hatred boiled over on May 13, 1940, when a band of students from Guadalupe College came out onto the streets to protest against the Japanese. That protest turned into looting of Japanese homes and businesses. Some eyewitnesses to this infamy said that APRA party members were very involved in it all. I don’t know the details, but ironically the only Peruvian president who’s ever publicly apologized to the Japanese community is the former president Alan García [1985-90, 2006-11], who was himself from the APRA party. They do say as well that some people took advantage and joined the protests because they wanted the Japanese businesses to fail, so they encouraged the mob to loot them.

Well, thank God many friends and people in the community helped their Japanese neighbors (paisanos) to hide and take refuge from the rampaging mob, because the police inexplicably failed to show up until hours later, when it was too late to stop any of it.

You might say that this was just down to chance, and that the government just overstepped the mark in inciting people to hatred, were it not for the fact that afterward, the first administration of president Manuel Prado Ugarteche [1939-45] declared war on Japan before the US did. In its efforts to please the US government the Peruvian government even started to seize assets belonging to the Japanese, as well as all their schools, including the Nikko School in Lima (which nowadays is the Colegio Teresa Gonzales de Fanning).

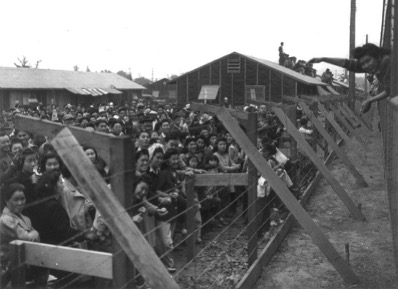

Concentration camps in the US where Japanese immigrants from all over the Americas were sent

Once Japan and the US were at war with each other, blacklists started to be drawn up that included well-to-do Japanese businessmen and traders, community leaders and anyone who could be considered a threat to national security…. Though I would say really it was a case of posing a threat to the interests of the governing oligarchy. That’s how it came about that more than 2,200 Japanese were sent from Latin America to concentration camps in the US. Of that group, the country that deported most people was Peru, which sent more than 1,500 people to camps at Crystal City in Texas. Wives and children were included: even if children who had been born in Peru, they were still sent to the camps.

A lot of Japanese had to go into hiding to avoid being deported. Some went up to the Peruvian highlands (sierra) so they couldn’t be found, others got help from friends who hid them in their own houses. My father tells how his godmother, who was of Italian extraction, helped his family to hide during the persecution and the looting.

Large concentration camps in the US where Japanese civilians and their nisei children [second-generation children of Japanese descent] were held

They say that one reason the US asked Latin American governments to send their Japanese populations to the concentration camps was so they could use them to exchange for US prisoners. Because for the US Army it was hard to capture Japanese soldiers because they would commit suicide rather than let themselves be taken prisoner. So that’s why they decided to use Japanese civilians who had nothing to do with the war, to make prisoner exchanges.

Once the war finished, Peru was one of the countries that refused to take in the Japanese people – and their Peruvian children – that it had previously deported. For a few years there was even a complete ban on any Japanese citizen entering the country. The Japanese who had immigrated to Peru never stopped loving their adopted country even after they were deported: they had made Peru their home, and they found ways to return. Some of them had to do it by traveling to Bolivia and entering the country by crossing the Amazonian jungle. Many had to wait until the mid-1950s before they could rejoin their families in Peru. The ban also affected the second-generation Japanese-Peruvian (nisei) children who had been sent to Japan before the war, and wanted to return to Peru to reunite with their families, but couldn’t. It was different in Argentina, where president Perón sent a plane to Okinawa especially to collect all the Argentine nisei children who had been stranded there because of the war.

Another of the consequences of the confiscation of the schools and the breaking off of relations with Japan by the wartime government of Manuel Prado Ugarteche was that the children of the Japanese community lost their chance to carry on learning Japanese. That’s why Peruvian nisei children who are under 80 years of age don’t speak Japanese, unlike the nisei generation in other countries. The rupture in diplomatic relations meant that for years there was no Japanese consulate in Peru, so children of Japanese extraction weren’t registered and couldn’t acquire the right to Japanese nationality.

Talking to lots of people over 80 years of age, when you ask them what is the memory that has most marked them in their life, for most of them it’s those acts of vandalism that they were forced to witness. There are also those who had to suffer the consequences of the deportation or persecution of family members. Many have memories of being somewhere between 5 and 10 years of age, and their parents sending them down to the bottom of the house to hide, but even so they can’t forget the noise made by that mob looting everything it found in its path.

Many years later the US government acknowledged that it had been partly responsible for this harm to innocent people, and they paid USD 20,000 compensation to all those Japanese who had been taken prisoner But they didn’t do the same for the Peruvian ones: they only agreed to give them USD 5,000, because they weren’t US citizens.

Years after the looting, the first government of president Fernando Belaunde [1963-68] decided to hand over a plot of land, of about 10,000 m2, in the Residencial San Felipe district of the capital, Lima, as compensation for the confiscation of all the Japanese schools. That’s the land where they later built what today is the Peruvian-Japanese Cultural Center.

All of these things lead me to reflect on how a war that’s happening thousands of kilometers away can affect innocent people who have nothing to do with the conflict, because some bad people take advantage to further their own political and economic self-interest, putting paid to the fruits of years of hard work by families who built themselves up by the sweat of their brow. In spite of everything, those families didn’t lose themselves in hate or resentment of those who did them so much harm. On the contrary, they decided to start again and build themselves up from nothing, due to their conviction that anything is possible through hard work, effort and decency.

Fernando Nakasone Nozoe

Saqueos y Deportaciones y aun así, siguieron amando al Perú

Publicado por Fernando Nakasone el May 15, 2016

Era mayo de 1940 mi obaachan (abuela) de 17 años y mi ojichan (abuelo) de 20 años quienes hasta ese entonces trabajaban en una chacrita que tenía mi bisabuelo en Esquivel, decidieron abrir su primer pequeño negocio en Huaral, gracias al apoyo de algunos paisanos, abrieron una pequeña encomendería y como al lado de la tienda había un espacio grande mi abuelo decidió convertirlo en estacionamiento pero “estacionamiento para burros” la primera vez que lo escuche me dio mucha risa pero efectivamente a Huaral llegaban sobre todo los fines de semana mucha gente desde sitios muy alejados a hacer sus compras, como llegaban en burro al irse a hacer sus compras lo dejaban “estacionado” en el espacio que mi abuelo había acondicionado.

Lamentablemente a pocos días de haber inaugurado su pequeño negocio un 13 de mayo de 1940 una turba de gente llena de odio azuzada por el gobierno y por los medios saqueo la pequeña encomendaría de mis abuelos y de todos los japoneses de la ciudad, mi abuela embarazada de 17 años llevaba en su vientre a mi padre aún con 4 meses de gestación al ver como entraba esta turba rompiendo y robando todo lo que encontraban solo le quedo esconderse y acurrucarse debajo de uno de los mostradores. Este hecho no fue aislado, sino que ocurrió también en otras ciudades del país y principalmente en Lima con un saldo de más de 600 familias afectadas y más de 10 japoneses muertos.

Desde que se inició la inmigración en 1899 los japoneses empezaron trabajando de peones en las haciendas en las peores condiciones pero a base de esfuerzo y trabajo poco a poco fueron saliendo adelante, muchos lograron primero alquilar y luego comprar sus propios pequeños campos de cultivos, posteriormente fueron migrando a la ciudad convirtiéndose en prósperos comerciantes, ese éxito en los negocios japoneses empezó a causar la envidia y el fastidio de la clase oligárquica dominante que los empezaron a ver como una amenaza a sus intereses.

Es así como en 1936 el gobierno empieza a poner en prácticas leyes que iban contra el ingreso de más japoneses al país deteniendo abruptamente el proceso de inmigración hacia el Perú, se empezaron a dictar leyes en las cuales los japoneses no podían traspasar sus negocios a otros extranjeros y como sus hijos a pesar de haber nacido en Perú no tenían la nacionalidad peruana no podrían heredar los negocios de sus padres, todas estas medidas se fueron dando con el fin de detener el progreso de los japoneses, esta situación de odio y envidia se fue volviendo más crítico con el ingreso del Japón al eje tripartito Roma-Berlin-Tokyo en donde el odio hacia los japoneses se fue incrementando.

Es así como se fueron lanzando rumores de que los japoneses eran en realidad espías del imperio japonés y que se estaban armando para atacar el palacio de gobierno y algunas ciudades del país. Resulta increíble imaginárselo pero la población se creyó el cuento y esa mezcla de paranoia y odio explotó un 13 de mayo de 1940, en donde una turba de estudiantes del Colegio Guadalupe salieron a las calles a protestar contra los japoneses y finalmente esta protesta derivó en saqueos a las casas y negocios de los japoneses, algunos testigos de esta infamia contaban que mucho tuvieron que ver miembros del partido aprista, desconozco los detalles, sin embargo irónicamente el único presidente peruano que ha pedido disculpas públicas a la colectividad japonesa ha sido un miembro del partido aprista, el ex presidente Alan García. Se dice también que en estas protestas aprovecharon para unirse la gente que quería echarse abajo los negocios de los japoneses incitando a la turba a saquearlos.

A Dios gracias hubo muchos amigos y vecinos que ayudaron a sus paisanos japoneses a esconderse y protegerse de la incontenible turba y en donde la policía inexplicablemente nunca se apareció hasta horas después cuando los hechos ya estaban consumados.

Podría decirse que esto fue un hecho fortuito y que al gobierno se le paso la mano en incitar el odio a la población sin embargo posterior a estos hechos, el gobierno de Manuel Prado Ugarteche le declara la guerra al Japón antes que los Estados Unidos inclusive con el fin de ganarse la pleitesía del gobierno Norteamericano, el gobierno empieza a confiscar los bienes de los japoneses y también todos los colegios de la colectividad entre ellos la Escuela Lima Nikko (actualmente Colegio Teresa Gonzales de Fanning).

Al iniciarse la Guerra entre Japón y los Estados Unidos se empiezan a confeccionar listas negras que incluían a prósperos comerciantes y empresarios japoneses, así como dirigentes y toda persona que en teoría sería una amenaza a la seguridad nacional (yo diría más una amenaza a los intereses de la clase oligárquica gobernante). Es así como se envía desde Latinoamérica más de 2,200 japoneses a campos de concentración en los Estados Unidos de este grupo el país que más colaboró con la deportación fue el Perú enviando más 1,500 personas a los campos de Cristal City en Texas, en los que incluían a las esposas y los hijos que aun habiendo nacido en el Perú igualmente fueron enviados a estos campos.

Muchos japoneses tuvieron que esconderse para evitar ser deportados, algunos se fueron a la sierra para no ser encontrados, muchos también recibieron la ayuda de amigos que los escondieron en sus casas, mi padre cuenta que su madrina de origen italiano ayudó a la familia a esconderse durante las persecuciones y los saqueos.

Se dice que una de las razones por la que Estados Unidos pidió a los gobiernos latinoamericanos el envío de japoneses a sus campos de concentración, era para canjearlos con los prisioneros americanos, pues para el ejército norteamericano le era difícil capturar prisioneros a los soldados japoneses pues estos antes de ser capturados preferían suicidarse, es por ello que deciden utilizar a civiles japoneses que nada tenían que ver con la guerra para realizar este intercambio.

Terminada la guerra, el Perú fue uno de los países que se negó a recibir a los japoneses y sus hijos peruanos que había deportado, prohibiendo durante varios años inclusive la entrada al país de cualquier ciudadano japonés, los japoneses que habían inmigrado al Perú a pesar de haber sido deportados nunca dejaron de amar el país que los recibió, ellos ya habían hecho del Perú su morada y buscaron la manera como regresar, algunos tuvieron que hacerlo viajando a Bolivia e ingresando al país atravesando la selva amazónica, muchos tuvieron que esperar hasta mediados de los años 50 para poder volver unirse con sus familias en Perú. Esta prohibición afecto también a todos los niños nisei que habían sido enviados antes de la guerra a Japón y quienes deseando regresar al Perú para reunirse no lo pudieron hacer, caso diferente sucedió con Argentina en donde el presidente Peron mandó especialmente un avión hasta Okinawa a recoger a todos los niños nisei argentinos que habían quedado atrapados en la guerra.

Entre otra de las consecuencias generadas por las confiscaciones de los colegios y el rompimiento de las relaciones con Japón por parte de gobierno de Manuel Prado Ugarteche fue que los hijos de los japoneses perdieron la oportunidad de seguir aprendiendo el idioma japonés es por ello que los nisei menores de 80 años no hablan el idioma japonés caso diferentes sucede con los nisei de otros países. El rompimiento de relaciones diplomáticas hizo que el consulado japonés se retirara del Perú por muchos años impidiendo que los hijos de los japoneses fueran registrados en el consulado japonés y puedan tener el derecho de la nacionalidad japonesa.

Conversando con muchas personas mayores de 80 años al preguntarles cual es el recuerdo que más a calado en su vida, para la mayoría fueron los actos de vandalismo que tuvieron que presenciar y también quienes tuvieron que sufrir las consecuencias de la deportación o la persecución de sus familiares. Muchos recuerdan que aún tenían entre 5 a 10 años cuando sus padres para protegerlos los mandaron al fondo de la casa a esconderse, pero aun así no pueden olvidar el ruido de la turba saqueando todo lo que encontraba a su paso.

Luego de muchos años el gobierno norteamericano aceptó haber incurrido en esta vejación hacia personas inocentes e indemnizó con $20,000 a todos los japoneses que habían sido hecho prisioneros sin embargo no hizo lo mismo de la misma manera con los peruanos a quienes solo reconocieron darles $5,000 por el hecho de no ser ciudadanos norteamericanos.

Años después de estos saqueos, el primer gobierno de Fernando Belaunde decide entregar un terreno de aproximadamente 10,000 m2 en la residencial San Felipe en resarcimiento a las confiscaciones de todos los colegios japoneses, es finalmente en este terreno donde se construiría el ahora Centro Cultural Peruano Japonés.

Estos hechos me llevan a la reflexión de como una guerra que ocurría a miles de kilómetros de distancia puede afectar a personas inocentes que nada tuvieron que ver con este conflicto, pero que sin embargo personas del mal aprovechando la coyuntura y simplemente por el interés político y económico pueden acabar con el fruto de años trabajo de muchas familias que con el sudor de su frente pudieron construir. A pesar de todo lo ocurrido nunca quedo el rencor ni el odio hacia las personas que tanto daño les hicieron muy por el contrario decidieron nuevamente construir todo desde cero convencidos que con trabajo, esfuerzo y honradez todo es posible.

Fernando Nakasone Nozoe

Instagram

Instagram