Andrew Hasegawa

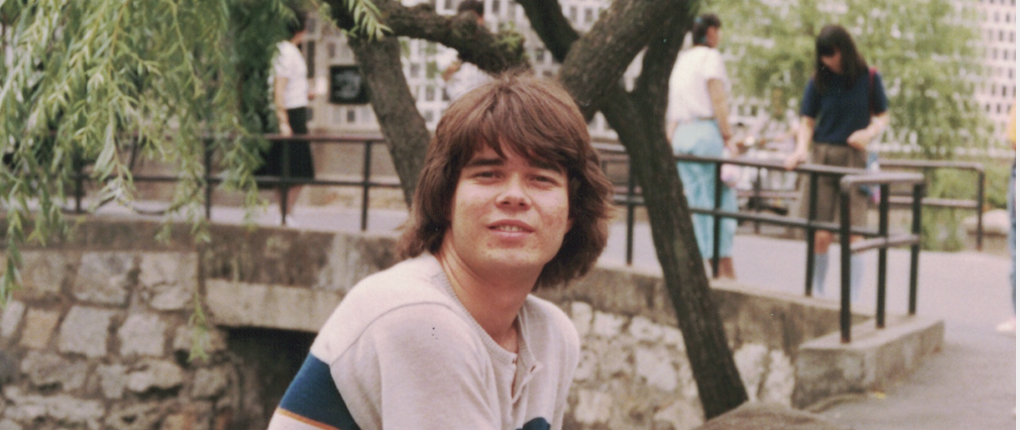

Andrew Hasegawa as a student in Japan, 1983.

Andrew Hasegawa, these days of Melbourne, is not Japanese. On that point, he is quite emphatic: “I don’t see myself as Japanese because I’m not. I’m just a citizen of Australia who happens to have an unusual ethnic background. And I’ve spent a lot of time learning about it.”

A lot of time indeed. To hear him tell it, “My Japanese heritage has driven my life in some respects.” Today, Andrew is researching connections between his own history and the global context of stories, triumphs, and injustices experienced by Nikkei in several countries. For him, what began as a search for meaning in a mysterious heritage has blossomed over a lifetime into two careers and an adventure spanning continents.

It began in childhood, as many things do. Though occasionally bullied by classmates for his Japanese surname, “my father always said to me, from when I was a little boy, ‘you must not change your name.’ And I didn’t understand why.” Nor did Andrew yet know what had driven the other sons of his immigrant great grandfather, save Andrew’s own grandfather and father, to change their Japanese names. The learning continued with youthful summers in the 1970s, spent in his grandmother’s home in Geelong, in the State of Victoria. It was then that she first shared stories of Hasegawa Setsutaro, her father-in-law, once of Otaru, Hokkaido. Says Andrew, “I became more and more curious. My grandmother could only tell me so much. A lot of what she said was accurate or quite accurate and some of it was totally misleading. And one day I decided to find some answers. I wrote a letter to the public records office of the State of Victoria, asking if they had a record of when my great grandfather arrived. And to my surprise, several weeks later, I received a letter saying that he had arrived in February 1897, on the Yamashiro Maru.”

Setsutaro’s father was a samurai retainer, “possibly serving one of the lords from the Niigata area” before the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Many former samurai families in the 1870s, including the Hasegawa, were drawn north by government work under the Hokkaido Development Commission.

Setsutaro himself was born in 1871, his family being registered in Otaru, “a pokey little fishing village” at that time, where facilities “weren’t particularly good.” The family clearly valued education, as demonstrated by letters he later received from home, written in a highly formal cursive script, which today perhaps “only 0.01 percent of the Japanese population could read,” and by Setsutaro’s impeccable English script. Andrew’s grandmother maintained that Setsutaro had attended university, which in the late nineteenth century could only have been Tokyo Imperial University. Andrew explains, “He became a schoolteacher and was very interested in learning English. He came to Australia and worked as a household helper for a very wealthy Melbourne family, to learn English. For various reasons, he never returned. I think he intended to return, but marriage and children prevented it.”

Andrew’s own interest in his heritage was reignited in university, where he began studying Japanese. Becoming an exchange student in Osaka, then Kyoto, Andrew confesses to a “checkered record as an undergrad.” Nonetheless, he entered the honours stream, intending to study the Japanese outcast community, the burakumin. The topic was still taboo at the time: “you’re not supposed to know about it. So [the proposal] was rejected two or three times.” Eventually he made the needed contacts and received approval for his topic. Andrew persevered and graduated with a first class honours degree in Japanese Studies and History. Following a job offer from a securities firm, he spent the next 26 years working the financial markets in Tokyo and later in Hong Kong. Returning to Australia in 2012, Andrew set up an importing business for Japanese retail and wholesale goods. Having never lost sight of his heritage and now reestablished in his home country, he then began his research as a historian anew, publishing a series of articles on his family with Nikkei Australia starting in 2014.

When Andrew first learned of the Past Wrongs, Future Choices project, he began to consider more intensely the connections between his family past, the injustices faced by Japanese Australians before and during the Pacific War, and the concomitant wrongs inflicted on the Nikkei of other Allied countries. He began wondering, “How could I involve myself?”

Andrew explains, “The skillset I have is doing research. Of course, you have to prove to yourself after many years away from university is that you can still do research. So, I started digging around in the archives, which I’m very familiar with.” Attending community-based meetings of PWFC-affiliated scholars, he was surrounded by “various professors of this, that and the other.” Despite his hiatus as a scholar, Andrew was soon in the thick of it, “learning the language of the Past Wrongs, Future Choices partnership.” After receiving a PWFC award to support his efforts, Andrew was motivated to seek a residency at the University of Victoria, just as his project was beginning to take shape: “I said, ‘I want one.’ But to say you want one, you have to have a proposal. I knew what my proposal was, so I just went for it.”

So, which chapter in the saga of Nikkei resilience does Andrew seek to tell? In genre, it is a legal drama, as much a tale of courage as of government subterfuge and duplicity. Andrew had originally stumbled across the story of one Katsumata Kojiro, a Japanese Australian farmer who fought a legal battle up to the level of the High Court in early 1946, threatening to invoke a writ of habeus corpus to retain the right to his home in the face of looming postwar deportations. In late 2021, the 75-year embargo on key papers for the Katsumata case in the national archives was ended. Andrew pounced. He says, “There was one memo in particular which told us what happened between the High Court, the government, and Katsumata’s legal team. And I said, ‘that’s it. This is juicy. No academic has ever picked up on this.’”

Doubtless the information would have been of academic interest decades earlier, had it been public knowledge. Although Katsumata’s counsel did ultimately secure for him his right to remain in Australia, very few of the country’s other Nikkei were so fortunate. By June 1947, only 335 people identified as being ethnically Japanese or part-Japanese. Why did other Japanese Australians not invoke their legal rights, as Katsumata had? As Andrew describes, they were left unaware of their options for a very deliberate reason: in exchange for his freedom, Katsumata’s legal team agreed to end its proceedings and keep the public in the dark. Says Andrew, “Why do they ask for no publicity? Because the government lives in fear of the judiciary. You can imagine if that became public, and suddenly a whole bunch of internees [including Germans and Italians] start making applications for writs of habeas corpus. It had the potential to derail the deportations of Japanese and others.” The leading advocate of the so-called ‘White Australia Policy’ at that time, Immigration Minister Arthur Calwell, had placed his thumb on the scales and secured the outcome that he and others like him so desired.

The story was vastly different in the United States. Mitsue Endo’s successful claim of habeus corpus in the US Supreme Court in December 1944 triggered the release of more than 70,000 imprisoned Nikkei. Says Andrew, “It’s front-page news in the New York Times. It’s not a secret.” Andrew’s working paper reveals how divergences in government policy and collective representation between the two countries resulted in vastly different outcomes for the Japanese-descended populations, even where the same legal mechanism was used.

Andrew has found the collaborative element of his PWFC residency to be invaluable, particularly in his friendship with historian Lon Kurashige and his meeting with legal scholar Eric Muller, who provided crucial insight into the American half of the story. He also has no intention of stopping his collaborations at this stage. Andrew declares, “You could just finish your working paper and go off into the woods, but for me, that won’t happen. I’ll just keep exploring it.” In addition to assisting the Archives Cluster with its research, Andrew is also working with Ciel Dong and Nao Uda on “raising some funds from the Australia Japan Foundation with a view to creating a transnational exhibition which would roll out in Japan and Australia.”

Above all, Andrew highlights the transnationality and inclusivity of PWFC: “I didn’t expect to be awarded the residency because I don’t have a PhD, I’m not a post-doctoral fellow, I’m not halfway through writing my PhD, I haven’t published a journal article, and it’s been a long, long time since I’ve been to university. That the partnership could embrace me was very satisfying. I’m humbled.”

This article was written by Aaron Stefik from an interview with Andrew Hasegawa.

Instagram

Instagram