Project Director’s Message: A Visit to Tatura, Australia

As many as 13,000 people were interned at the Tatura site in southeastern Australia during World War II. Made up of a network of separate camps spread across a small region, Tatura held prisoners of war captured in Europe and the Pacific, Jewish refugees interned as enemy nationals, and civilians deemed a security threat by Australian authorities. Among those interned were approximately 1,000 people of Japanese descent, held in a segregated “family camp.” They included Japanese Australians as well as Nikkei families displaced from elsewhere in the Pacific: New Guinea, The Dutch East Indies, Singapore and Malaya. Tatura is one of four sites where Nikkei civilians (some 4,000 in total) were interned in Australia (the others are Loveday, Hay, and Cowra).

My head is spinning after a visit to Tatura last week. I had the opportunity to go in the company of the wonderful staff of Museums Victoria — Pat Deacon, Gurmeet Kaur, and Nadya Tkachenko who work in Education and Outreach Programs, and Moya McFadzean, a senior curator at the museum who has been its principal contact with the Past Wrongs, Future Choices. Moya took photographs during our trip that have helped me to draw together some of my thoughts.

The history of the camps is preserved and presented at a small museum in the town of Tatura, a two hour drive due north of Melbourne. A small and dedicated staff of volunteers runs the museum, which also presents a history of irrigation in the region. This combination struck me as somewhat dissonant, accustomed as I am to the presentation of internment as an important historical wrong. I found myself thinking about the various frames – historical injustice, immigration, local history — within which histories of internment are told.

This prison block held internees at Tatura who ran afoul of camp authorities. It is the most substantial structure still standing at the site. If you look closely you may see to the right of the cells a nest of barbed wire, which remains strewn about the site. The cells have no windows. With the notable exception of the Cowra breakout, in which hundreds died, I’ve found that Australian internment is often portrayed as relatively benign in its implementation, with narratives emphasizing, for example, positive relations between guards and internees. This cell block made me wonder: how are such assessments arrived at?

On the rest of the site, the remnants of the built environment of internment are the foundations of shacks and other facilities. Having visited former internment sites in Canada, these surprised me. How many sites of internment poured foundations for their barracks? What does this tell us about how the facilities were understood?

This Kurt Winkler drawing is at the Tatura Museum, though its label suggests that he drew it during a stint at another camp, Loveday. A profile of Winkler appears in Monash University’s Internment & Beyond digital exhibition, explaining that he was a German ex pat in England who found himself on the wrong side of enemy lines in 1939. After attempting to send him to internment camps in Canada (the ship sank, with Winkler among the survivors), the British shipped him to Australia. “No other . . . artist left so complete a record of internment at Tatura,” explains the exhibition. This drawing suggests the cross-cultural relations that characterized internment in Australia, as well as at select camps elsewhere (for example Angler in Ontario, where Japanese Canadians were incarcerated alongside Germans and Italians). How much do we know about these relationships?

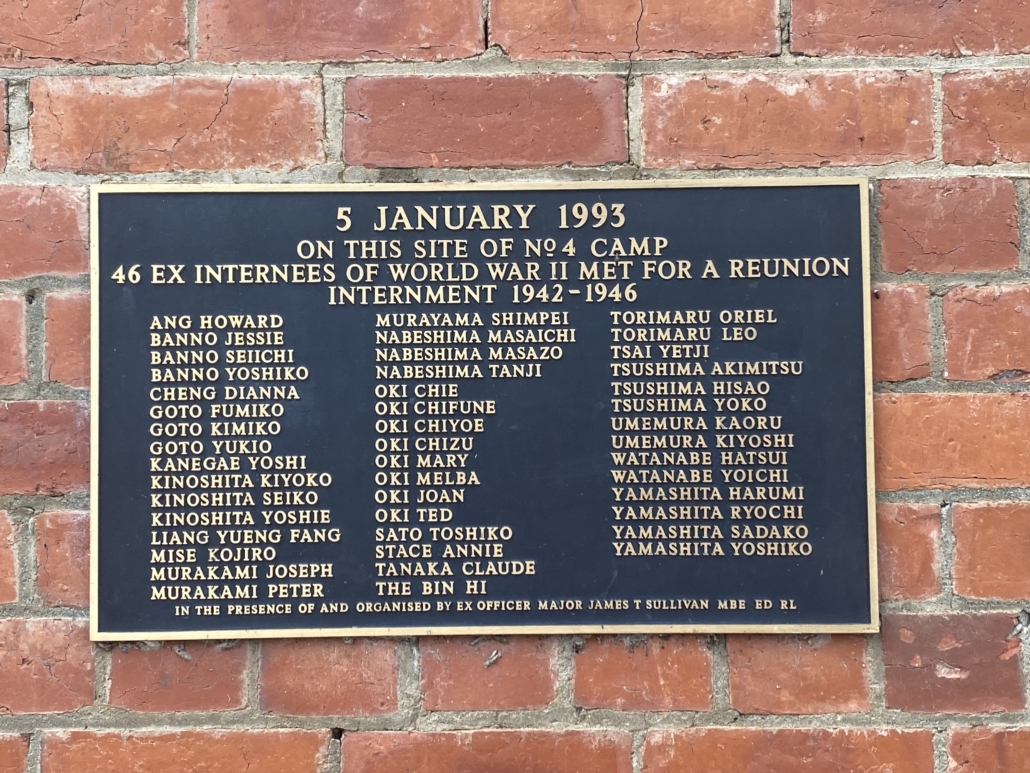

Finally, those of us interested in memory and commemoration may want to learn more about this reunion, which occurred at Tatura in 1993. Our guide at the site, George Fergusson, believes that at least some in attendance came from Japan, to which the large majority of interned Japanese Civilians in Australia were deported at the end of World War Two.

Instagram

Instagram